| Aspect | Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) | Sleeve Gastrectomy |

|---|---|---|

| Image |  |

|

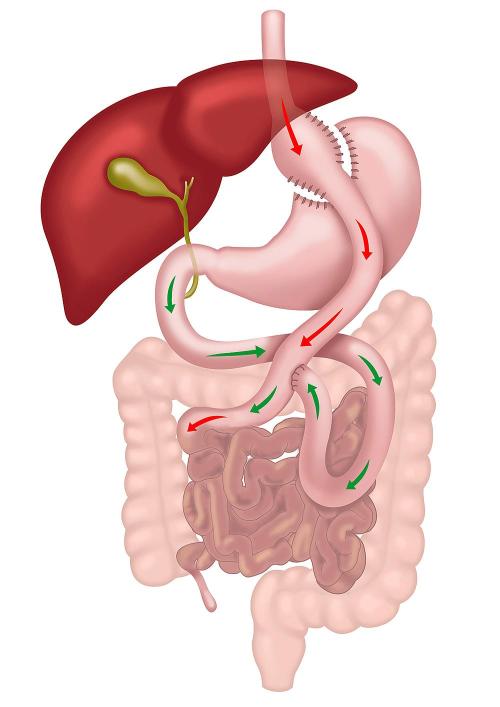

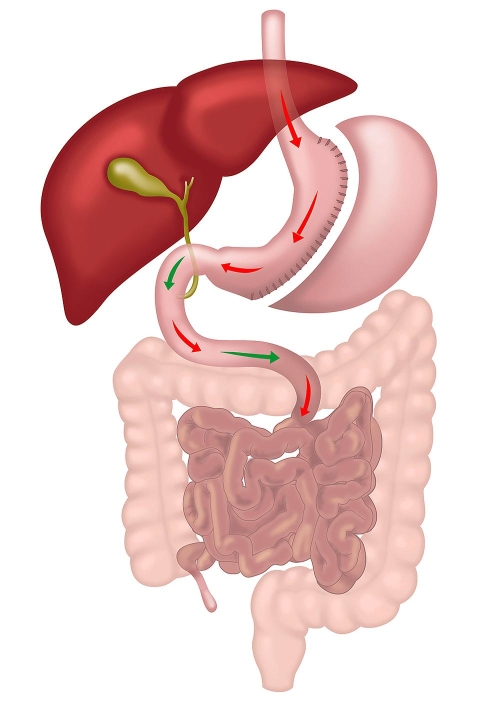

| How the Operation is Done | Performed laparoscopically, RYGB involves creating a small stomach pouch and connecting it to the small intestine, bypassing most of the stomach and duodenum with two joints. | Performed laparoscopically, Sleeve Gastrectomy involves removing a large portion of the stomach, leaving a narrow, tube-like stomach that limits food intake. The small intestine is not altered. |

| Modality of Action | Restrictive and Metabolic. The metabolic component is stronger than in sleeve due to change in small intestine anatomy. | Restrictive and Metabolic. The metabolic component is weaker than in gastric bypass as the small intestine is not altered. |

| Weight Loss Potential | Higher weight loss potential, achieving approximately 30-40% of total body weight due to dual mechanisms of caloric restriction and metabolic changes. | Moderate weight loss, approximately 25-35% of total body weight, primarily through restriction of food intake. |

| Improvement in Metabolic Conditions | Greater improvement in conditions like type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia due to significant hormonal changes affecting insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. | Significant improvement in metabolic conditions, but generally less pronounced than with RYGB, as metabolic effects are secondary to the restrictive nature of the procedure. |

| Management of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD) | Effective for GORD management as it reduces acid production and reroutes bile away from the stomach pouch, lowering the risk of acid reflux. | May worsen or give rise to GORD symptoms due to the high-pressure system created in the sleeved stomach, making it less suitable for patients with existing GORD. |

| Risk of Nutritional Deficiencies | Higher risk of deficiencies due to bypassed sections of the small intestine, requiring lifelong supplementation and monitoring for vitamins and minerals. | Lower risk of deficiencies, though supplementation is recommended. Nutrient absorption is less impacted as the small intestine is not bypassed. |

| Complexity of Procedure | More complex, involving two anastomoses and significant rerouting of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to a higher risk of complications and a longer learning curve for surgeons. | Less complex, primarily involves reducing the stomach size without altering the intestinal tract, which generally leads to fewer complications. |

| Risk of Marginal Ulcer and Bowel Twist | Small risk of marginal ulcers at the anastomosis sites and potential for bowel twists or internal hernias due to altered anatomy. | No risk of marginal ulceration and bowel twist, as the procedure does not alter the small bowel. |

| Can Take Anti-inflammatory Medications? | No, lifelong restriction due to risk of marginal ulcer. | Yes |

| Dumping Syndrome | Common due to rapid gastric emptying into the intestine, leading to symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and dizziness. | Rare, as the stomach maintains a more natural function without rapid emptying into the intestine. |

| Limitations on Endoscopic Procedures | ERCP and other endoscopic procedures are challenging due to altered anatomy, which complicates access to the biliary and pancreatic ducts. | Normal endoscopic access is maintained, allowing easier management of biliary and pancreatic conditions. |

| Reversibility | Reversible, but the reversal process is complex and involves significant surgery. | Non-reversible; however, it can be converted to other operations like RYGB or SADI if needed. |

| Hospital Stay | 2-3 nights on average due to the complexity of the procedure and need for monitoring. | 1-2 nights on average, as the procedure is less invasive with fewer potential complications. |

| Good For | Patients with severe obesity, type 2 diabetes, and those with GORD or at risk of developing it. | Patients with moderate obesity without severe GORD, especially those seeking a less complex surgical option. Also as a first step in very big patients. |

Join Our Weight Loss Surgery Seminar

Interested in taking control of your health? Join our free seminar to learn about weight loss surgery options.

Tuesday, 24 February 2026

6:00 PM – 7:30 PM

Suite 13, 42 Parkside Cres, Campbelltown NSW 2560

Compare Bariatric Operations

Discover the differences between various obesity surgery options, from effectiveness to recovery times, in this comprehensive guide. Learn which procedure might be best suited to your health needs and lifestyle.

Frequently Asked Questions about Gastric Sleeve

Get answers to common questions about sleeve gastrectomy, covering everything from procedure details to expected outcomes. Understand what to expect and how this surgery could support your weight loss journey.

Frequently Asked Questions About Gastric Bypass

Explore key insights into the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, including how it works and what to expect post-surgery. This FAQ guide addresses common questions to help you make an informed decision about your weight loss options.

Join Our Bariatric Support Group

Our support group is dedicated to supporting those on their bariatric surgery journey. Gain insights, share experiences, and find encouragement to help you achieve your health and weight loss goals.

Why Grazing is Bad

Understand why grazing can hinder weight loss and affect your bariatric surgery outcomes. This guide explains the impact of frequent snacking and offers strategies to maintain healthy eating habits.

Why Roux en Y Gastric Bypass Improves Heartburn

Learn how the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass can effectively reduce acid reflux symptoms. This article explains the mechanisms behind the surgery’s success in alleviating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Pre-Op Diet Class

Prepare for bariatric surgery with our pre-op diet class, designed to guide you on essential dietary changes for a successful surgery and recovery. Learn key strategies to optimize your health and support your weight loss journey.

Our Technique for Gastric Sleeve

Explore each step of the sleeve gastrectomy procedure to understand how this effective weight loss surgery is performed. This guide walks you through the surgical process, from preparation to the final stages of the operation.

What is the Best Weight Loss Operation?

Choosing the right bariatric surgery can be life-changing, but with so many options, how do you decide? This article helps you understand which procedure might be best for you, based on your unique needs and goals.

FAQs about Hair Loss After Weightloss Surgery

Are Your Weight Loss Goals Realistic?

Bariatric Support Group

Connect with others on the same journey. Our support group offers guidance, motivation, and expert advice for long‑term weight loss success.

Who: Current and future Southwest Bariatrics patients, plus family and supporters

Where: The George Centre in Gregory Hills

Join the Support GroupAddress

Southwest Bariatrics

Suite 13, 42 Parkside Cres, Campbelltown NSW 2560

Suite 14, The George Centre, 1A-1B The Hermitage Way, Gledswood Hills, NSW 2557

surgery@southwestsurgery.com.au

Mo-Fr: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm